Learning to treasure Martha's Vineyard's "low green prairies of the sea.”

Salt marshes don’t always inspire affection, but when they do, it can be intense. In 1902, the Massachusetts naturalist Dallas Lore Sharp dedicated an essay to salt marshes in The Atlantic, calling them “one of the most satisfying drinks of color my eyes ever tasted.” There was, he continued, “no other reach of green so green.”

The marsh is both boundary and buffer — at the edge of the sea, it dampens wave action from storms, sequesters carbon, filters water, offers finfish and shellfish a protected nursery, and draws a sharp line at the end of many coastal walks.

“It’s a stunningly beautiful and productive habitat, visually, ecologically,” said Suzan Bellincampi, Mass Audubon Islands Director and another disciple of the marsh. “And the fact of the matter is, the land is more useful than most people can even imagine, especially now.”

Useful is an adjective that has waxed and waned in this landscape. To the Indigenous peoples along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, marshes have been indispensable, with whole ways of living timed to this coastal abundance, fish and shellfish used for food, wildflowers used for dye. Tribes including the Wampanoag continue as stewards in these ecosystems today.

Settlers found use for marshes, too, particularly in fishing and farming. They set their hogs loose to snort around the mud flats for clams, and fished themselves for eels — buckets, baskets and bushels full. “Eels ran so thick that we first thought them sea grass,” wrote a colonist in 1634. “Not of so luscious a taste as they be in England,” he sniped, but “wholesome for the body.”

Europeans harvested salt hay for their livestock and thatched houses with it. The hay harvest was set to the tides, first according to a trusted few with knowledge of the moon, later according to a farmer’s almanac. When the tides ran low, the cut grass would stay dry, and during these times, men with scythes would make hay, as they say, while the sun shone.

The cattle and horses already had a taste for marsh grass, and the colonists figured that “the air of the sea whets their appetites.” Horses wore special shoes for walking in the marsh muck, wide wooden ones that spread their weight out as they trudged across the spongy peat.

One motivation for opening the great ponds on the South Shore of Martha’s Vineyard was to lower the water enough to harvest the salt hay — which included the soft “black grass,” Juncus gerardii, more accurately called the saltmarsh rush, as well as the plentiful saltmeadow cordgrass, Spartina patens.

Protecting this ecosystem can mean restoring tidal flow and remediating ditches, but it also means making room for the marsh to move — maintaining undeveloped land where new marsh can form as old marsh is lost, rising inland and upland with the level of the sea.

Sharp, the naturalist, loved these grasses, which “covered the marsh like a deep, thick fur, like a wonderland carpet into whose elastic, velvety pile my feet sank and sank, never quite feeling the floor. The tints, shading from the lightest pea green of the thinner sedges to the blue green of the rushes, to the deep emerald green of the hay-grass, merged across their broad bands into perfect harmony.” John Greenleaf Whittier called the vast marshes on the mainland “low green prairies of the sea.”

Salt hay was part of a resource-intensive colonial food pyramid, an insatiable need for one commodity, hay, to feed another, cattle, as cheaply as possible. As settlement pressed from the margins of the continent inward, chasing new business models, people in power began to think of salt marshes as a problem that needed solving. One rationale followed another for ditching, draining, and filling them.

In the 19th century, Federal Swampland Acts encouraged the “reclamation” of wetlands for farmland, and developers in booming cities used garbage and gravel to make marshes into new neighborhoods like Boston’s Back Bay. In the 20th century, after mosquitos were identified as a vector for disease, the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps went into almost every marsh in the Northeast and dug ditches for standing water drainage — the ruler-straight channels we see today.

In total, Massachusetts has lost 40% of its salt marsh in the last 200 years, according to a study of historical maps. Another estimate, by the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management, put the net loss of marsh on Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, and the Elizabeth Islands over just the last century or so at about 375 acres, an area about the size of Squibnocket pond.

“Before people really understood the value of salt marshes, we kind of destroyed them,” Bellincampi said. “And now it’s a coastal resilience imperative.”

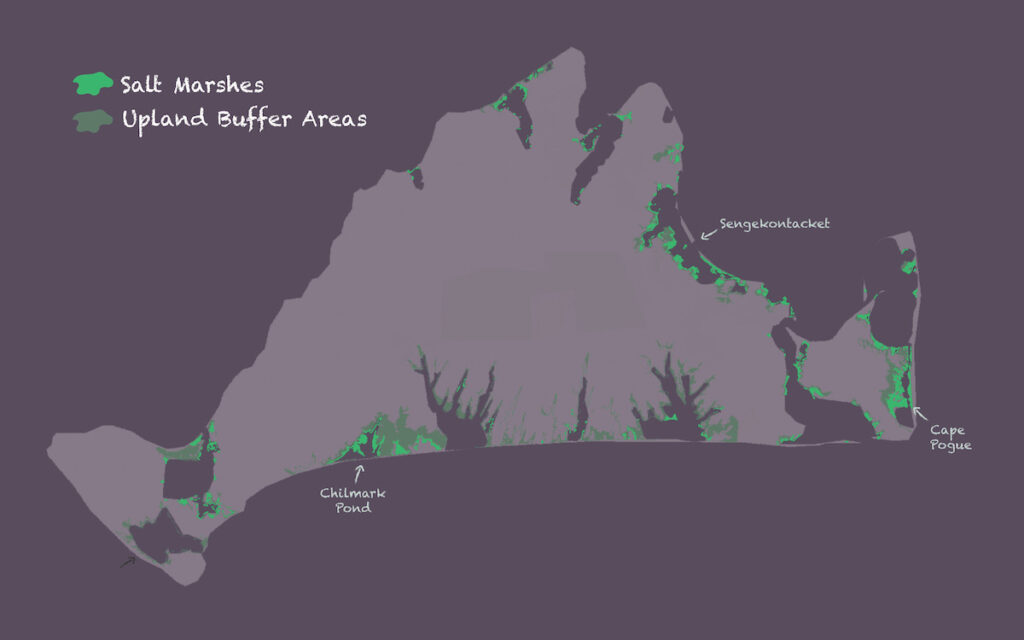

Extensive marshes remain on Martha’s Vineyard on Chappaquiddick, in Pocha Pond and Cape Pogue bay, and between Oak Bluffs and Edgartown, in Sengekontacket, where they are protected by a long barrier beach. Other patches can be found all over the island — hugging inlets and shorelines of Menemsha, Katama Bay and Tashmoo, and scattered in nooks across the Island’s great ponds.

These landscapes are more protected now, and their losses have slowed thanks to federal and state legislation. But drawing lines around the marsh doesn’t prevent it from changing in dramatic and sometimes alarming ways. Marshes are highly adaptable, but one thing they have not evolved to do is stay still.

Sergio Fagherazzi, a coastal geomorphologist at Boston University who studies salt marsh deposition, has written that salt marshes are “ephemeral landforms at the geological time scale,” that are “constantly reworked by coastal processes within a few thousand years, in a rejuvenation process.”

Marshes build up vertically, as vegetation traps sediment and generations of plants die and become peat. They also travel horizontally, as marsh grasses spread their rhizomes underground, send their seeds by wind and tide, or break off pieces of themselves that become new plants. They are eroded by coastal storms, and sometimes even calve like glaciers, splitting off “marsh bergs” that float away to wind up somewhere else.

They expand quickly seaward or landward as conditions allow, and contract even more quickly when conditions require. They can fill in behind a newly formed barrier beach, or inch up a tidal creek as freshwater retreats. They are ecosystems fine-tuned to a changing coastline, to the flux of sediment generated by elemental forces. “Compared to the history of Earth, a salt marsh resembles a gorgeous butterfly,” Fagherazzi writes. “After emerging from the cocoon, it extends its wings under the morning sun, rises in the sky during the day, and when the night falls, it folds its wings and dies.”

Protecting this ecosystem can mean restoring tidal flow and remediating ditches, but it also means making room for the marsh to move — maintaining undeveloped land where new marsh can form as old marsh is lost, rising inland and upland with the level of the sea. I read that shoreline change arrives as a “pulse” of big, sudden storms over the “press” of the steadily higher ocean. Together these forces are an “ecological ratchet,” pushing freshwater trees and plants out and up, pulling salt grasses in.

The state has identified upland areas on Martha’s Vineyard that are crucial to protect as marshes rise, and the Martha’s Vineyard Commission is planning and mapping for the future to come. A recent study of Sengekontacket, funded by the Village and Wilderness Project, identified around 170 acres of land fringing the pond that could become marsh in the next 30 years, if preparations are made — enough to offset even a total loss of what’s there now.

Bellincampi often takes preschoolers into the Sengekontacket wetlands around Felix Neck. “They actually love to get their rubber boots on,” she told me. “It’s just amazing watching them stomp through the marsh. You never know what you’re going to find out there — all the life, the little fish darting around, the holes for the crabs, the Spartina patens and alterniflora, depending on where you are in the marsh, the salt marsh asters and all the flowers. Damselflies, dragonflies.” I, myself, am partial to seaside goldenrod, Solidago sempervirens, a perennial which grows at the edge of the marsh, blooming in dense bursts of yellow.

“Osprey like to hang out on the edge,” Bellincampi added, “on the beetlebung at Felix Neck. And then they’ll just go down and get fish.” There are owls there, too. Sharp, the naturalist, encountered one at dusk and wrote: “What was I that dared remain abroad in the marsh after the rising of the moon? That dared invade this eerie realm, this night-spread, tide-crept, half-sealand where he was king?”

The saltmarsh sparrow is another bird whose way of life is carefully tuned to the insects, grasses, and tides of this landscape. This bird nests in the high marsh, and races against the moon to lay eggs, hatch chicks, and raise them to fledglings in the few weeks before a big tide returns to drown the whole operation. Four out of every five saltmarsh sparrows have disappeared since 1998.

The sparrow, like the coal mine canary, indicates bigger problems on the horizon, as climate change causes continuing sea level rise and an increase in major storms. If the marsh disappears, a lot more will be lost. “It’s the buffer, it’s the protection zone,” Bellincampi said. “You think of big strong trees, but the strength of the marsh is these little grasses and mud and detritus.”

“We have to protect and do our best to preserve what we have,” Bellincampi said, “because we’ve lost so much of it.”

The salt marsh, insect-laden, squelching with mud, has managed to gather a lot of admirers — myself among them. But I can’t do it justice in words like a gilded-age naturalist. “When I catch that first whiff of the marshes after a winter,” Sharp wrote, “the smell of it stampedes me. I gallop to meet it, and drink, drink, drink deep of it, my blood running redder with every draught.”

What you can do

- Check out this StoryMap on Vineyard marshes by Chris Seidel and Dan Doyle of the Martha’s Vineyard Commission

- Take a walk in the marsh

- Read the Sengekontacket case study (great maps)